Christian Nasulea, Executive Director of think tank IES Europe, sits down with Arthur Laffer, the renowned economist behind the Laffer Curve, for an interview for the youtube channel of Epicenter, a network of European free market policy think tanks.

“EU taxation should be around 10% of GDP,” argues American economist Arthur Laffer, adding that Europe is “nowhere near its growth potential because government has simply become too big and too expensive.” He also maintains that “inequality is a natural in this world”, and warns that attempts to iron out economic differences through ever-higher taxes and transfers risk undermining the very prosperity politicians claim to defend. In his view, the EU’s prevailing model of high public spending, heavy taxation, and detailed regulation is not protecting prosperity but steadily eroding it.

Laffer’s prescriptions are unapologetically radical by Brussels standards. He calls for a flat, broad-based value-added tax of about 10% as the primary source of revenue, minimal or no income tax, and a total tax burden capped at roughly 10% of GDP. He wants government employees put on performance-based pay linked to economic growth rather than bureaucratic expansion. And he rejects EU-wide tax and regulatory harmonisation outright, insisting that competition and experimentation among member states are essential if Europe is to remain globally competitive.

Americans have among the lowest tax burdens among OECD countries https://t.co/2WoxO9UWU8 pic.twitter.com/9gixtUuVHi

— Catherine Rampell (@crampell) January 28, 2024

The cost of big government

Laffer traces Europe’s underperformance to the size and scope of its public sectors. High regulatory compliance costs, complex rules, and redistributive spending, he argues, have created incentives that reward the growth of administration rather than the creation of wealth. In such an environment, entrepreneurs, investors, and skilled workers often encounter obstacles instead of opportunities.

He stresses that governments, like firms, respond to incentives. When ministries and agencies are effectively rewarded for processing more paperwork or launching new programmes, they will tend to prioritise those activities over fostering productivity and innovation. The result is a steady expansion of bureaucracy that crowds out private initiative while failing to deliver commensurate gains in living standards.

To reverse this dynamic, Laffer proposes performance-based compensation for public-sector employees. Instead of linking pay and promotions to headcount, budgets, or regulatory output, he suggests tying them to measurable economic outcomes such as growth, employment, and investment. Shifting incentives in this way, he believes, would encourage policymakers and administrators to focus on policies that actually enhance prosperity rather than merely expanding their own apparatus.

French tax hikes tapped out, spending cuts inevitable, says audit office https://t.co/SyFIGCtXZe https://t.co/SyFIGCtXZe

— Reuters (@Reuters) February 19, 2026

Taxes that work for growth

At the heart of Laffer’s vision is a radical simplification of Europe’s tax systems. Rather than relying on a mix of high-income taxes, corporate levies, social contributions, and assorted surcharges, he advocates a single, low, broad-based VAT of about 10% as the main revenue instrument. This would be combined with minimal or no income tax and an overall tax take limited to around 10% of GDP.

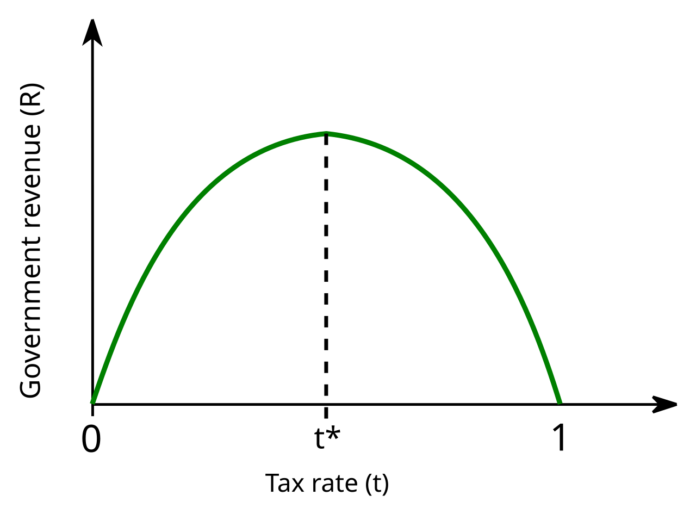

Laffer argues that high marginal tax rates directly discourage work, investment, and entrepreneurship, especially in an era when capital and skilled labour can move easily across borders. In his analysis, Europe risks losing both if it persists with punitive tax levels and complex regimes that are costly to navigate and easy to game.

A low, flat VAT, he contends, would sharply reduce distortions in labour and capital markets, while eliminating many loopholes and opportunities for avoidance. It would also simplify compliance and make the true tax burden more transparent for households and firms. By providing predictability and clarity, such a system would, in his view, create a more conducive environment for long-term investment and innovation.

Sources of government revenue in the OECDhttps://t.co/p8Nlg3Lilw pic.twitter.com/G0BEI0hNV1

— Tax Foundation (@TaxFoundation) July 8, 2021

Competition, not harmonisation

Laffer is particularly critical of current efforts to harmonise tax policy across the EU and to push for global minimum corporate tax rates. While these initiatives are often justified on grounds of fairness or the fight against “race to the bottom” dynamics, he believes they mainly serve to lock in high tax levels and reduce policy experimentation.

Instead, he calls for robust tax competition among member states. When countries are free to try different fiscal approaches, they generate valuable evidence about what works in practice. Jurisdictions that adopt more growth-friendly tax structures can attract investment and talent, creating pressure on others to reform or risk falling behind.

This competitive logic extends beyond taxation to regulation, particularly in emerging areas such as artificial intelligence. Laffer warns that heavy-handed, one-size-fits-all EU rules on new technologies risk stifling innovation before it has a chance to take root. Allowing member states to test different regulatory models, he argues, would make Europe more adaptable and better positioned to capture new opportunities in fast-moving sectors.

"The EU’s control over taxation is tightening" – New article by @pietercleppehttps://t.co/yZ5FKa2pLq

— BrusselsReport.EU (@brussels_report) February 16, 2026

Rethinking spending and redistribution

On public spending, Laffer urges Europe to refocus on what he sees as the core functions of the state: education, the judiciary, and defence. Large-scale redistribution, industrial policy, and expansive welfare programmes, he contends, tend to inflate government without generating proportional economic benefits.

His “transfer theorem” highlights the trade-offs involved in redistribution. Taxing one group to give to another, he argues, weakens incentives on both sides of the transaction: those who pay face reduced rewards for work and investment, while those who receive have less reason to increase their own output. Although such policies may reduce measured income inequality, he believes they do so at the cost of lower overall growth.

In Laffer’s view, durable improvements in living standards are driven primarily by economic expansion rather than by compressing income differences through progressive taxes and transfers. He therefore calls for a cautious approach to redistribution, warning that policies aimed at equalising outcomes can inadvertently erode the very prosperity they seek to share.

Harm reduction, not punishment

Laffer also advocates for behavioural taxation of harmful products such as tobacco. He favours a harm-reduction approach: higher rates on the most dangerous products combined with lower rates on safer alternatives like vaping products or nicotine pouches.

The goal, he argues, should be to encourage consumers to switch to less harmful options rather than to punish addiction or disproportionately burden low-income groups. As with broader tax policy, he opposes uniform EU rules in this area and prefers to let member states experiment and adjust their approaches based on real-world outcomes.

Taken together, Laffer’s proposals outline a consistently pro-growth, decentralised vision for Europe: smaller government, leaner and more focused public spending, low and simple taxation, and vigorous competition among jurisdictions in both tax and regulatory policy. As the EU reflects on its competitiveness in an increasingly demanding global environment, it should at least seriously consider elements of this agenda. Whether or not policymakers fully embrace Laffer’s prescription, engaging with these ideas could help the Union design a framework that rewards work, innovation, and investment — and ultimately delivers stronger, more sustainable prosperity for its citizens.