They do not seem to be able to stop. This week, EU climate ministers reached an agreement on yet another new EU climate target, this time for 2040. Despite some concessions on a few points, EU Member States agreed to reduce CO₂ emissions by 90 per cent compared to 1990 levels.

A few bright spots: the introduction of the extremely expensive new CO₂ tax ETS2 for people that drive petrol or diesel cars or that heat their homes with gas will be postponed by one year, to 2028. EU Member States will also be allowed to offset a small portion – 5 per cent – of their own emissions by purchasing so-called carbon credits outside the European Union – at the expense of taxpayers, that is.

Bizarrely, a qualified majority of EU Member States voted in favour of this type of policy. Only Hungary and Slovakia voted against it. Belgium and Bulgaria abstained. Italy, Poland and Romania were somewhat resistant, but ultimately they backed the compromise. The other European governments are completely ignoring the growing opposition to this type of economically damaging climate policy.

The reason for taking decisions on this issue right now is the so-called ‘climate summit’ COP30 in Brazil. The European Commissioner responsible for climate policy, Wopke Hoekstra, reacted afterwards with delight that the EU would now be able to continue to play a ‘leading role’ in climate policy. He did admit, however, that high energy costs and social protest were the reasons for the watering down of the European Commission’s proposals.

COP30

The annual UN COP climate summit is kicking of this month. Last year, this “COP” climate summit took place in Baku, a hotbed of oil and gas exploration. This year, it will take place in Belém, Brazil, in the middle of the Amazon region, forcing Brazilians to cut down forests to build new roads and airports to make the summit possible. Tens of thousands of hectares of protected Amazon rainforest were felled to build a new four-lane motorway.

The United Nations’ climate conference, COP30, in Brazil 🇧🇷 begins in less than two weeks.

Tens of thousands of acres of protected Amazon rainforest were felled earlier this year to build a four-lane highway to alleviate anticipated traffic congestion.

“Saving the planet.” 🌴🪓 pic.twitter.com/1pXVOEQvto

— Chris Martz (@ChrisMartzWX) November 2, 2025

The fact that the U.S. under Donald Trump once again left the Paris Climate Agreement does not seem to bother European governments, nor does the fact that China and India are continuing to expand their coal-fired power plants. In China, for example, coal capacity increased by 80 to 100 gigawatts this year. Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, and the eastern state of Assam, which recently withdrew incentives for clean energy projects, are planning to sign purchase agreements in the next two months for a total of at least 7 gigawatts of coal-fired energy, to be delivered by 2030. Climate neutrality? “Net Zero”? Thanks but no thanks, India and China say.

None of this seems to matter to the EU. Full of enthusiasm, the President of the European Commission thanked Brazilian President Lula, stating: ‘Brazil is showing great leadership. Whether it is about putting a price tag on carbon. Or fighting for our forests.’

Thank you for bringing us together at the gates of the Amazon dear @LulaOficial.

As COP30 begins, you can count on Europe's full support.

Brazil is showing great leadership.

Whether it is about putting a price tag on carbon. Or fighting for our forests.

Today we also… pic.twitter.com/sXCoYBfJJo

— Ursula von der Leyen (@vonderleyen) November 6, 2025

It would be funny if it weren’t so sad. Apart from the EU’s bungling with its own new bureaucratic deforestation directive, which is causing anger both inside and outside Europe, Brazil is not exactly a model pupil when it comes to deforestation. Soy cultivation, for example, is responsible for major ecological damage.

Climate policy making in the land of soy cultivation

In August, the Brazilian authorities decided to suspend the so-called “Amazon Soy Moratorium” (ASM). This arrangement is a sectoral agreement under which commodities traders agreed to avoid the purchase of soybeans from areas that were deforested after 2008. According to studies, this contributed to reducing the overall rate of deforestation in the Amazon region. What is remarkable about the arrangement is that it was voluntary and brought together farmers, environmental activists and international food companies. It allowed soy production to increase significantly without destroying the Amazon region and is estimated to have prevented 17,000 km² of deforestation.

The WWF warns about this that ‘Without proper safeguards, the soybean industry is causing widespread deforestation and displacement of small farmers and indigenous peoples around the globe.’ Although soy for oil production is planted in an area of 125 million hectares, or almost 30% of oil crop area worldwide, it is only supplying 28% of the vegetable oil demand, which suggests considerable inefficiency..

NGOs have therefore complained that soy production in Brazil contributes significantly to the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, both directly through the clearing of forests for new soy farms and through the displacement of small farmers who then move to forest areas to engage in subsistence farming. Infrastructure for the development of this sector also plays a role, of course, as does the use of pesticides and the impact that soy cultivation has on water consumption and waste processing. Furthermore, the Brazilian agricultural sector, and therefore also soy cultivation to a large extent, is responsible for about three-quarters of the CO2 emissions of the country where the global climate club is now gathering.

A democratic deficit

In an article about COP30, the BBC interviewed Claudio Verequete, a simple Brazilian worker. He complains about the new road built to bring climate policymakers to Belém: ‘Everything was destroyed,’ he says, gesturing at the clearing, adding: ‘Our harvest has already been cut down. We no longer have that income to support our family.’ He claims he has received no compensation from the state government and is also concerned that the construction of this road will lead to more deforestation in the future, now that the area is more accessible to businesses.

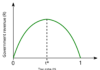

In Europe, many people agree more with Claudio’s point of view than with those of the European Commission, which continues to boast of being a ‘climate leader’. In recent years, public support for expensive climate policy has however declined significantly in Europe. While in 2018, 35 per cent of Europeans still considered climate and the environment to be among the two most important challenges facing the EU, that figure has now fallen to a mere 10 per cent. The contrast with what policymakers decide is striking. A true democratic deficit.

Climate sanity, finally

EU has been gripped in a decade-long climate panic

But it is now fading, leaving an opportunity to focus on sensible, affordable climate policies

Data: Eurobarometer since start 2010, percent naming climate/environment as one of two top issues for EU… pic.twitter.com/WEXeSqvDgl

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) November 5, 2025