Last month, the founder and owner of leading chemical giant INEOS made a major call upon European policy makers, both in the EU and the UK. Sir Jim Ratcliffe stated:

“I am calling on Europe’s politicians to make an ‘eleventh-hour’ intervention and save the chemical industry. (…)

Europe’s chemical industry is at a tipping point. The UK’s chemical production is already down 30%, German production is down 18% and French production is down by 12%. 21 major European chemical plants are scheduled to shut and eight out of ten of Europe’s chemical giants are not investing in the continent.”

In its press release, INEOS does not exactly mince its words when describing the root of the problem, thereby calling for drastic immediate changes to EU climate policies, to which the UK continues to align:

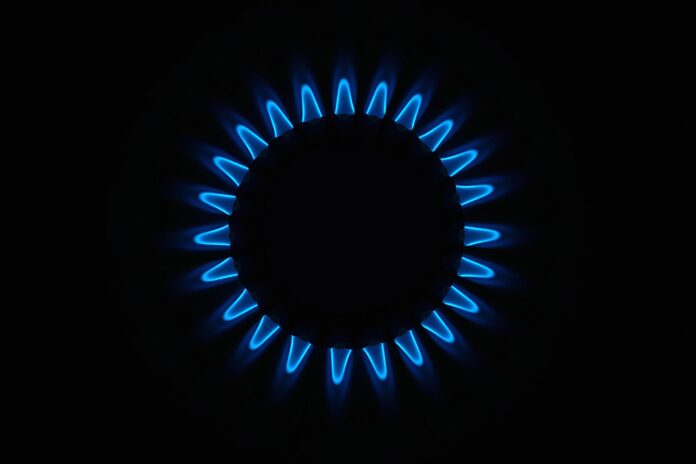

“We urgently need to bring the continent’s energy and carbon taxes in line with the rest of the world and challenge one-sided tariffs. If this isn’t done, there won’t be a chemical industry left to save. (…) Astonishingly, Europe’s chemical industry is being driven out of its global markets because of its own self-imposed costs. Europe’s gas prices are four times higher than the US and, together with the continent’s high carbon taxes and US tariffs, the industry cannot compete.”

We don’t want sympathy, we want action.

Hear from Sir Jim as he outlines three critical interventions needed to prevent Europe sleepwalking into deindustrialisation👇🏼

Watch the full interview: https://t.co/HuFpicR56c#SaveEUIndustry #ChemicalIndustryMatters… pic.twitter.com/W3W2znZdnd

— INEOS (@INEOS) October 16, 2025

Over the last few years, Europe’s chemical sector has seen large-scale divestment. This week, US chemical company Celanese, which has been in Belgium since 1965, announced it will cease operations at its Lanaken plant in Belgium. It thereby complained that “European regulations are penalizing us”. Specifically, reportedly, a key issue is the possibility that, at the upcoming COP11 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), to be held in Geneva on November 17–22, the EU could support and extend a complete ban on cigarette filters to the single market.

The chemicals company notes that “the intent to cease operations at Lanaken stems from “a strategic review to ensure the long-term sustainability of Celanese’s acetate business, which has faced challenging conditions, including declining demand and increasing uncertainty in the regulatory environment for tobacco products.”

Also energy prices played a big role, however, as it explained that “the intent to close our production operations was influenced by several factors, including the unfavorable climate for investment, rising energy costs, and strict and rapidly changing regulations in the chemical industry.”

One can only wonder why the Belgian government is not standing up more forcefully against these regulations at the EU level, and why no European government is currently demanding a big change in energy policy, which is at the heart of the current ills of European industry.

The natural gas price is absolutely key for the chemical sector, which forms the bedrock of all other industry in Europe. While changing energy policies unfortunately takes a lot of time, it is simply incredible that the cost of the EU’s carbon taxation arrangement, the “emissions trading scheme” (ETS), is about twice the total cost of the US natural gas price. While the European natural gas price is about four to five times the US price, companies in Europe need to compete with Asia with a natural gas price that is 50 percent higher.

Why is EU industry bleeding? The cost of the EU's de facto climate tax (ETS, a cap and trade scheme) is about twice as big as the total US natural gas price (red vs blue bar), which is only about 1/5 of the EU's natural gas price: https://t.co/t66Vmwj6xA

— Pieter Cleppe (@pietercleppe) September 22, 2025

Sir Jim thereby does not shy away from singling out the elephant in the room. He simply urges to “scrap” carbon taxes:

“First, remove the green taxes and levies from energy costs. Second, scrap the carbon taxes. And third, give us some tariff protection. We need actions, not sympathetic words or there won’t be much of a European chemical industry left to save.”

INEOS thereby points out that the EU’s current policies also harm its climate ambitions:

“Europe’s net zero ambitions will also be damaged if its chemical industry collapses. Oxford Economics believes that if European chemicals production is replaced by imports from China and the US, carbon emission will rise and the greater distances needed to travel will further increase greenhouse gas emissions.”

In fact, a comparison with the United States, which lacks a similar ETS, for the most part, reveals that it has managed to reduce CO2 emissions per capita relatively more than the EU since 2005. Likely, this is due to the U.S. shale gas revolution, which enabled to replace coal with shale gas, which is currently banned in EU countries, despite the fact that these happily import shale gas from America at high prices, while stifling domestic gas exploration. At least, this comparison suggests that a more technologically friendly policy approach can also deliver environmental goals, while avoiding the taxation and central planning pushed for by the European Commission.

The first von der Leyen Commission truly doubled down on EU climate regulation, but until this day, the European Commission is resisting major changes to these policies.

It is fighting tooth and nail to continue with yet another climate target, this time by 2040, and it still has not proposed to lift the EU’s de facto ban on combustion engines by 2035. This despite the warnings by the likes of Oliver Zipse, CEO of BMW. He said in September: “If the current emission rules remain in place, the car industry in Europe will be halved.”

It is puzzling why there is absolutely no sense of urgency in Brussels or national capitals.

On the contrary, the current debate isn’t so much about abolishing current climate policies. It is about avoiding overly stringent new climate policies. The European Commission has proposed to extend the EU’s ETS climate tax to consumers, dubbing this “ETS2”. According to this ill-advised plan, anyone who drives a diesel or petrol car or heats their home with gas will see their bills go up with hundreds of euros more per year. Many EU member states want to scrap it, but the Commission is trying with all its might to continue with it anyway.

NEW – Exploding electricity and gas prices: The "energy transition" is driving Germany towards deindustrialization — NZZ pic.twitter.com/xCj6KsODTn

— Disclose.tv (@disclosetv) November 1, 2025

By agreeing CBAM, which stands for “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism”, the EU has in fact admitted that its own industry is suffering from EU climate policies. The arrangement attempts to compensate domestic European industry for this by imposing new protectionist climate tariffs on certain imports. CBAM is however notoriously bureaucratic, and it thereby also punishes European companies – apart from the obvious damage resulting from more expensive imports. In practise, the European Commission is now admitting to the downsides of CBAM. Right before the Dutch election, EU Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra pointed out that he has made sure to “exempt 95 procent of companies” from CBAM, calling this “a success of less regulatory pressure, but one can hardly boast that the original plan was perfect.”

The fact that the EU is bombarding trading partners that do not follow its own suicidal climate policy with customs tariffs is also not exactly positive for EU trade policy. US President Donald Trump already managed to secure concessions on CBAM, but last Summer, this led to a demand by South Africa to also be exempted. After all, African economies are at risk of being hit hard by CBAM. South Africa’s Presidential Climate Commission has estimated that CBAM would reduce African exports to the EU by 30-35% by 2030, representing a value of €1.7 to €2.1 billion. In this regard, India recently complained that it is ‘almost impossible’ to comply with all the regulations the EU wants it to follow in exchange for an EU-India trade deal.

Similarly, Trump also managed to get concessions from the EU regarding its EU anti-deforestation directive, which had in fact already been challenged by the Biden administration. These new European rules ban the import of goods if producers fail to prove that no forests were felled in their production, something which comes with a lot of bureaucracy. The European Commission has in September proposed to delay the implementation of the directive, blaming an IT system issue. Reportedly this may be due to US pressure.

Trading partners like Indonesia and Malaysia are large exporters of palm oil and thereby heavily affected by the new bureaucratic burdens that EUDR would impose. Malaysia considers it unfair that its imports are classified as “standard risk”, as opposed to the US classification of “low risk”, given that deforestation there has improved significantly, with NGOs recognising a reduction of 13 per cent last year.

Despite the pressure from the United States and despite increased discontent among public opinion in Europe, no major changes to the EU’s green policy rulebook have been implemented. Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and the UK form the heart of Europe’s chemical industry, but their governments do not seem to be in a rush to force a big change to EU climate policy either. Yes, a major summit was held in Antwerp early 2024, at the chemicals plant that INEOS shares with BASF, ending with a cry for help from industries seeking lower energy costs and less red tape to help revitalise Europe’s industrial landscape. In June 2024, Sir Jim complained that EU policy makers “are listening but I have not seen any changes”.

It seems nothing much has changed.

Time to scrap the EU's climate taxation scheme ETS:

"Just as European industry is in the doldrums, the acceleration and tightening of EU climate targets is arriving. Belgian manufacturing companies in the chemical, building materials, and steel sectors are also increasingly… pic.twitter.com/S8N0kksM3j

— Pieter Cleppe (@pietercleppe) October 15, 2025