In the United States, the Trump administration is considering whether to allow US tech company Nvidia to sell its advanced H200 AI chips to China, after some flip-flopping, with restrictions and relaxations of US semiconductor export controls following each other. No final decision has been made yet.

Proponents of restrictions, like academic Justin Sherman, maintain that a relaxation “signifies strategic vulnerability for the United States, undermining U.S. credibility on the security risks of Chinese technology.”

However, in reality, it looks like U.S. security is ultimately undermined by these kinds of protectionist restrictions, as such policies seem to have ended up benefiting Chinese competitors like Huawei. Reuters Daily Briefing describes how this Chinese tech company “has quietly shifted from a telecommunications giant to a chips manufacturer as NVIDIA’s biggest competitor. They have taken on crucial roles in the semiconductor supply chain and have continued plans to ramp up production and technological innovation. The most concerning aspect is China’s progress in open-source models and applications. Instead of faltering without access to American tech, they have adapted with their own technology and now threaten to replace American options.”

The Trump administration is weighing whether to allow Nvidia to sell its advanced H200 AI chips to China, marking a possible shift away from its earlier hard line on semiconductor export controls. Internal discussions are underway, but no final decision has been made.

The debate… pic.twitter.com/VcV8GYyItz

— Benzinga (@Benzinga) November 24, 2025

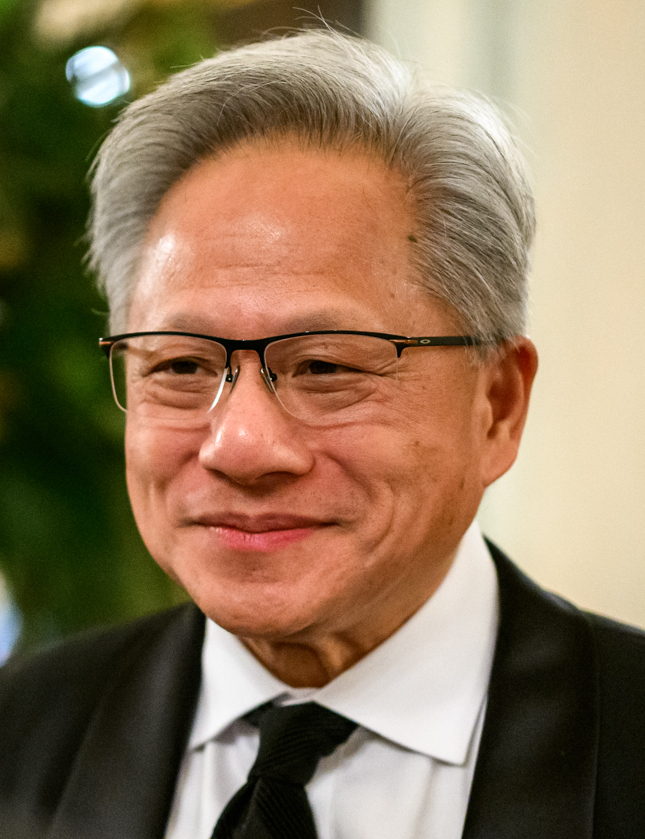

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has become increasingly vocal this year about the issue, bashing the 2022 policy of the U.S. Biden administration to restrict the export of Nvidia’s most advanced AI chips to China, which forced the company to design a processor that met the new limits. At the time, many industry experts were already skeptical, but Biden went ahead with it anyway.

Huang slams the outcome of the policy: “We went from 95% market share to 0%, and so I can’t imagine any policymaker thinking that that’s a good idea, that whatever policy we implemented caused America to lose one of the largest markets in the world”, noting that Nvidia is now “100% out of China.”

Instead, Huang thinks that striking a balance between maintaining U.S. tech supremacy and keeping access to China will require nuance rather than an all-or-nothing approach.

In April, his company was blocked by the Trump administration from selling some of its AI chips to China without licenses, but in August, the administration granted export licenses for certain Nvidia and AMD chips to China in exchange for 15% of the revenues.

Huang has furthermore warned that the US export controls have not only hurt Nvidia, but the whole of the U.S., arguing that China will “move on” with or without Nvidia’s chips, and that Chinese AI researchers will turn to homegrown chips and technology from companies like Huawei.

“The U.S. has based its policy on the assumption that China cannot make AI chips,” Huang has stressed, adding: “That assumption was always questionable, and now it’s clearly wrong.”

$NVDA SEEKS APPROVAL TO SELL B30A AI CHIP TO CHINA

CEO Jensen Huang said it’s “too soon to know” if the U.S. will allow it — but warned Huawei will dominate if U.S. chips are shut out. pic.twitter.com/pr8Qztdp8n

— Shay Boloor (@StockSavvyShay) August 22, 2025

In that respect, it is furthermore interesting to hear claims that the US export controls may have also pushed Huawei closer to the Chinese regime. Paul Triolo, partner and senior vice president for China at advisory firm DGA-Albright Stonebridge Group, told CNBC that “the export controls have ironically pushed Huawei into the arms of the Chinese government in a way that CEO Ren Zhengfei always resisted.”

From U.S. restrictions to Chinese restrictions

If the outcome of US semiconductor restrictions wasn’t bad enough, things took an even more unexpected turn early this month, with the Chinese government issuing guidance requiring new data centre projects that have received any state funds to only use domestically-made artificial intelligence chips. This is seen as dashing Nvidia’s hopes of regaining Chinese market share, as it provides local rivals, like Huawei, with yet another opportunity to secure more chip sales.

In August, publicly owned computing hubs across China were already asked to source more than 50 per cent of their chips from domestic producers. Policies like these are, according to a Reuters analysis “a clear escalation of competition, and a belief that Chinese manufactured chips have reached a comparable quality. Huawei plans to ramp up their chip production, and overall triple the AI chip output in China, further reducing NVIDIA reliance.” The analysis adds that “China has been catching up to the West in the most critical industries, like semiconductors and artificial intelligence, at an alarming rate.”

Nvidia boss Jensen Huang has not shied away from also criticising China for this, pointing out that “The advance of human society is not a zero-sum game.” Going forward, he thinks the U.S. needs “to make sure that people can access this technology from all over the world, including China.”

The United States can no longer undo the damage of its policies from the past, but it can avoid to repeat its mistakes, by staying away from tech protectionism.

Meanwhile in Europe

Also over here in Europe, it would be good to listen carefully to this successful entrepreneur, especially as influential voices like Financial Times columnist Robin Harding start arguing in favour of protectionism, because, in his words, “there is nothing that China wants to import.”

Even if it would be true that the Chinese Communist Party would see things like this and even if it would manage to push through mercantilist policies, that does not mean the West should help it with such a policy of “decoupling”. Restrictions on the basis of security are one thing, pursuing protectionist voodoo economic theories that go against the experience of the last few centuries that increased trade – even with adversaries – brings riches quite another.

The Dutch government’s seizure earlier this year of Nexperia, a Chinese-owned chipmaker based in the Netherlands, should serve as a warning sign. After the Dutch government took action in September over “serious governance shortcomings” and concerns over the European supply of semiconductors for cars and other electronic goods, China blocked exports of the firm’s chips, troubling major European manufacturers, like Volkswagen. In response, the Dutch government was forced to suspend its intervention.

The Nexperia effect.

Volkswagen prepares stopping production of Golf and Tiguan in Wolfsburg as of next week.

It will likely run out of chips by the end of the week. pic.twitter.com/VXBGVR8RRt— Thorsten Benner (@thorstenbenner) October 21, 2025

Surely, for the EU, it is a bit of a no-brainer how to restore competitiveness for its corporates if that is its goal. At the moment, the cost of the EU’s de facto climate tax – ETS, a cap and trade scheme – is about twice as big as the total US natural gas price, which is only about 1/5 of the EU’s natural gas price. Drastically reducing energy prices in Europe – also key for AI development – would go a long way already. Ending self-inflicted damaging policies should be the obvious thing to do before pondering tech protectionism.

Assuming that China or any other adversary will ultimately come up anyway with the tech that is being restricted and assuming that any protectionist policies will always come with some kind of retaliation is accurate: in the past, there is lots of evidence for both assumptions, as also higlighted above. In sum, zero-sum games tend to lead to zero positive results.