By Quinten Jacobs, a Belgian constitutional lawyer, and Adriaan Jacobs, a Belgian PhD researcher in cybersecurity at DistriNet (KU Leuven)

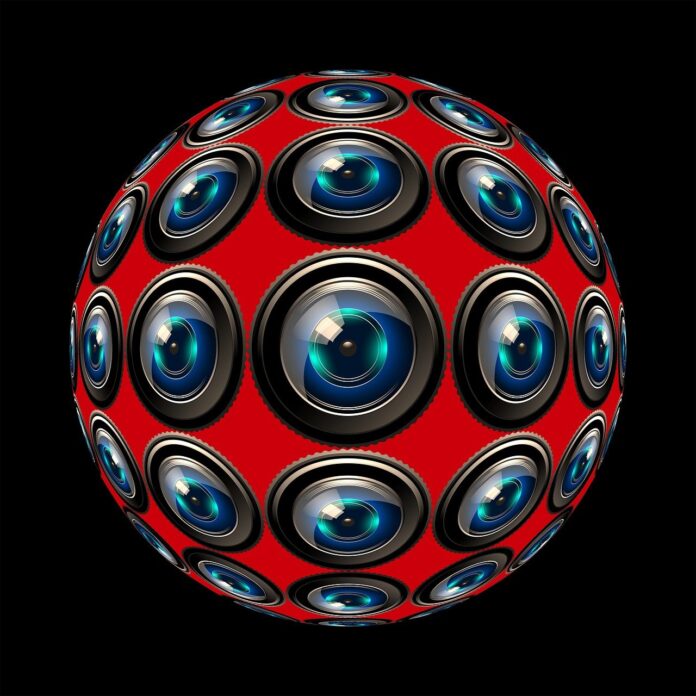

Are you okay with your photos on WhatsApp or Messenger being monitored? Under pressure from numerous privacy concerns, the EU proposal to screen private messages for images of child abuse has been systematically watered down in recent months. But even the latest Danish proposal still comes with major problems.

The European Union has been working for several years on a proposal to combat the spread of child abuse images. This is to be welcomed. But that does not mean that all means of achieving that goal are necessarily permissible.

Originally, the European proposal – dubbed “chat control” by critics – went so far as to require that every message sent between citizens online via Messenger or WhatsApp, for example, be scanned for images of child abuse. This is equivalent to the government opening every letter to check whether it contains photos of child abuse.

In other words, mass surveillance. Following opposition from Germany and France, among others, the proposal was watered down. After much deliberation, the Danish Presidency presented a new compromise proposal last month, on which also Belgium will soon have to take a position.

🇬🇧🚨Leak: Many countries that said NO to #ChatControl in 2024 are now undecided—even though the 2025 plan is even more extreme!

🗳️ The vote is THIS October.

👉 Tell your government to #StopChatControl!

Act now: https://t.co/vmOjnucT9i pic.twitter.com/DmfUqn5amk— Patrick Breyer #JoinMastodon (@echo_pbreyer) July 31, 2025

Various risks

The Danish proposal involves classifying applications that can be used to send private messages into three categories: applications with a low, medium and high risk of disseminating images of child abuse. Only the latter category is subject to strict obligations.

This sounds like a well-targeted measure, but the considerations and annexes to the proposal show that applications that use end-to-end encryption – a popular way of sending messages without the underlying companies being able to read them – will almost by definition be considered “high risk”.

Because WhatsApp and Messenger, among others, use this technology, the Danish proposal means that the most popular applications with tens of millions of users in the European Union will fall under the strictest regime.

In the worst case, these applications risk being required to scan every message from every user with a photo or URL link for images of child abuse. This is done via “client-side scanning”.

Every user would then have to install an update that allows the WhatsApp and Messenger apps to scan all uploaded images. Users who do not want this will no longer be able to forward photos or links.

Criminals will circumvent this

It goes without saying that criminals will easily circumvent such scanning by WhatsApp or Messenger by switching to other platforms that, temporarily or for a long period of time, manage to stay under the radar and continue to offer encryption without scanning.

In the best case scenario, this will become a classic cat-and-mouse game between the government and ever-changing applications.

In the worst case, the illegal market will simply move underground permanently.

Who will be monitored? You and me, users of WhatsApp and Messenger. There is no suspicion or even indication that these users are involved in child abuse, but according to the European proposal, all photos and URLs they send will be scanned.

Such an attack on privacy is not only constitutionally questionable, but also politically undesirable. At present, it concerns mandatory scanning of images of child abuse, but in the future, European legislators may decide to bring other content within the scope of chat control. It is a breach in the wall that can widen up more and more.

The Danish EU Presidency continues attempts to pass #chatcontrolhttps://t.co/IyHYvnYMTH @DanishMFA @bpreneel1

— Pieter Cleppe (@pietercleppe) July 30, 2025

Beach photos under suspicion

And even if criminals continue to forward photos on WhatsApp and Messenger, the technical feasibility of accurate assessment is highly uncertain. Either the application sets the bar very high for reporting, in which case chat control is ineffective. Or the application casts a wide net and there is a risk of many false positives, such as beach photos and photos of children, being reported, resulting in an overload of (human) services.

This is not inconceivable. Research shows that current detection systems would have to submit up to hundreds of millions of photos for manual verification every day. A foolproof system does not exist and, according to experts, is not likely to be developed in the near future.

What is possible, however, is the alternative put forward by the European Parliament during the negotiations on the Commission’s previous proposal. It calls for stricter intervention in content that is already public before private messages are scrutinised on a massive scale.

🇬🇧 Political blackmail: The EU Parliament is linking the extension of voluntary #ChatControl 1.0 to a Council agreement on mandatory #ChatControl 2.0. This forces a bad choice & contradicts the Parliament's own position against mass surveillance! https://t.co/ODntA0TFIh

— Patrick Breyer #JoinMastodon (@echo_pbreyer) August 8, 2025

For example, consideration could be given to requiring tech companies to invest in filters when uploading public files and to make it as easy as possible for users to report images of child abuse.

In any case, the distribution of images of child abuse is already illegal today and will remain so, whether chat control is introduced or not. The only question is whether we want to completely remove everyone’s right to confidential communication in exchange for a European law that is ineffective and only creates additional paperwork for companies. Our answer is no. Hopefully, Belgium’s answer at European level will be the same.

Originally published in Dutch by Belgian daily De Tijd.

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.